April 2023

Howard Rosenstein

In June 1981, Sharm was at the center of twin surges in diplomacy and diving tourism. Perhaps because it was an election year in Israel, Prime Minister Menachem Begin invited his Egyptian counterpart, President Anwar Sadat, for a summit in our small town. The diving season was in full swing, with visitors from around the world. National Geographic sent a team to cover the peace process and the impending Israeli handover of Sinai. Besides the diplomatic stars, Leonard Bernstein, the renowned conductor and composer—and frequent visitor to Red Sea Divers—was also visiting.

When the summit was announced, the government declared that Sharm would be closed to tourism. All our guests —Israeli and foreign — would have to leave the day before it started. Shocked by the sudden disruption, not to mention the hit to our pocketbook, we immediately protested. I used all my contacts to reach Begin’s military advisor, who at least managed to secure permission for the National Geographic team and Bernstein to remain.

Hundreds of journalists descended on Sharm, including crews from every major American and European television network. At the time, the town’s tourist accommodations consisted of a hotel, a motel, and five restaurants. Hearing that an American (me) was operating a local diving center, correspondents from ABC and NBC interviewed me for local color. When they saw Bernstein lunching with me at the diving center’s restaurant, they went wild. With some 15 journalists crowding around him, Bernstein lapped up all the attention.

An ABC-TV producer asked me to suggest stories that could be pursued while waiting for the summit. I told him I had heard that Israeli and Egyptian fishing boats, for the first time ever, were anchoring side by side just south of Sharm at Ras Mohamed, one of the world’s greatest diving sites. The producer jumped at the idea and chartered our dive boat to film the event. The maestro insisted on accompanying us. Bernstein was not an easy person to say no to, and the ABC crew loved the idea of his coming along.

Hearing of our plans, the National Geographic team of David and Anne Doubilet asked to join us, too. For us, having ABC News and National Geographic on our boat was the ultimate in media exposure.

The challenge now was how to sneak into an area that was absolutely off limits to tourist boats like ours. We decided our best course was to head northeast toward Tiran Island and then loop southwest to Ras Mohamed. It was bit nerve-wracking navigating the moonless night with our running lights off to avoid being spotted. Luckily, our radar picked up dots just off the coastline signaling that the fishing boats were indeed in place. The camera crews got their gear ready. I didn’t have a clue what would happen next.

Moving in total darkness, we positioned the boat near the largest cluster of fishing vessels. Bernstein was loving every minute of the experience, which was so alien to his usual world of glitz and glitter. When we were 50 meters away, I allowed the film team to turn on its lights and clicked on our powerful searchlights as well. The entire area was lit up, exposing a small fleet of boats of assorted sizes.

We must have freaked out the Egyptian fishermen as they surely thought we were the Israeli Navy launching a raid. With cameras running, we pulled up to the stern of the largest Egyptian vessel. Its deck was strewn with bait and fish innards; the fishermen, dressed in jellabiyas, were listening to Arabic music blaring from a boombox. I cautioned everyone on our boat against boarding until one of our Arabic-speaking crew members asked for permission.

Imagine my surprise when Bernstein suddenly jumped from our bow onto the Egyptian boat’s slippery aft deck and started mingling with the crew. I quickly hopped over the railing to join him. I found him dancing with the biggest, swarthiest fisherman on the boat, a man nearly twice Bernstein’s size. They were like whirling dervishes as they moved in synch to the Arab melodies. After a few minutes, the fisherman, who obviously had no clue that his dance partner was the most famous classical musician in the world, picked Bernstein up and kissed him on the cheek. All the while, the television and magazine crews were filming and clicking away. Bernstein stole the show from the unprecedented gathering of Egyptian and Israeli vessels.

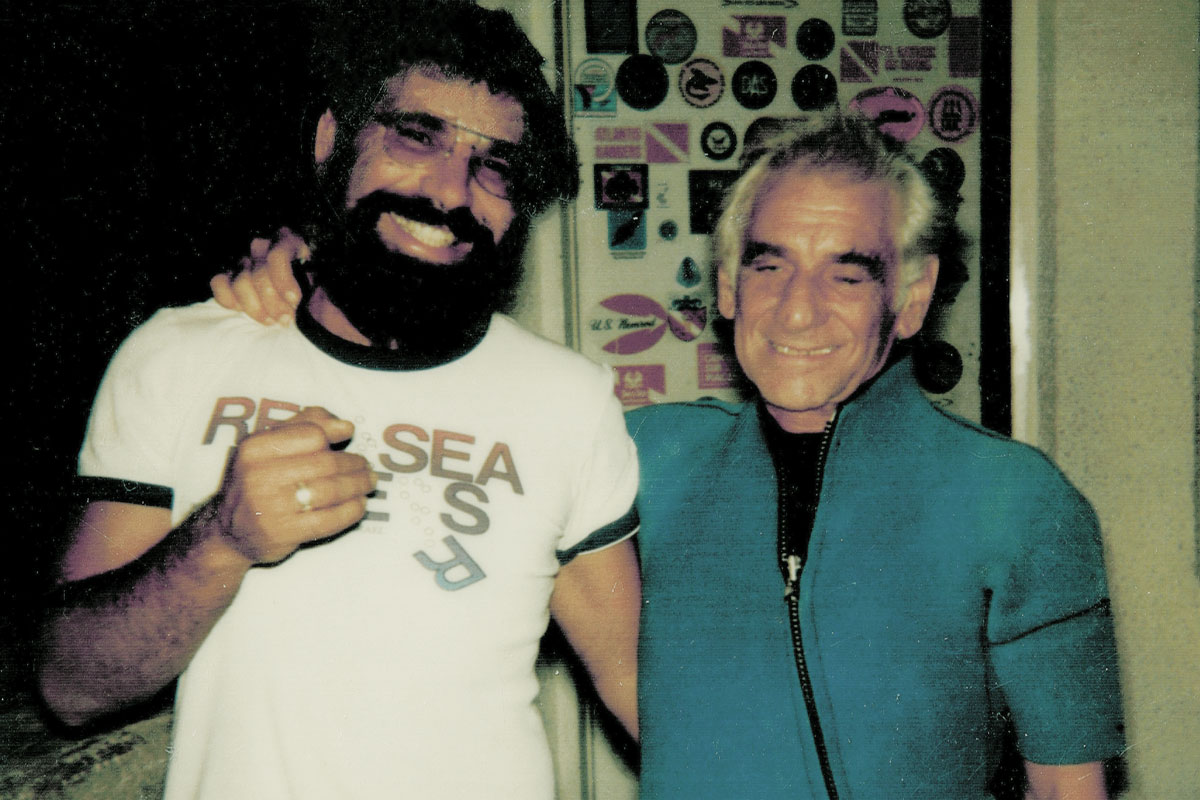

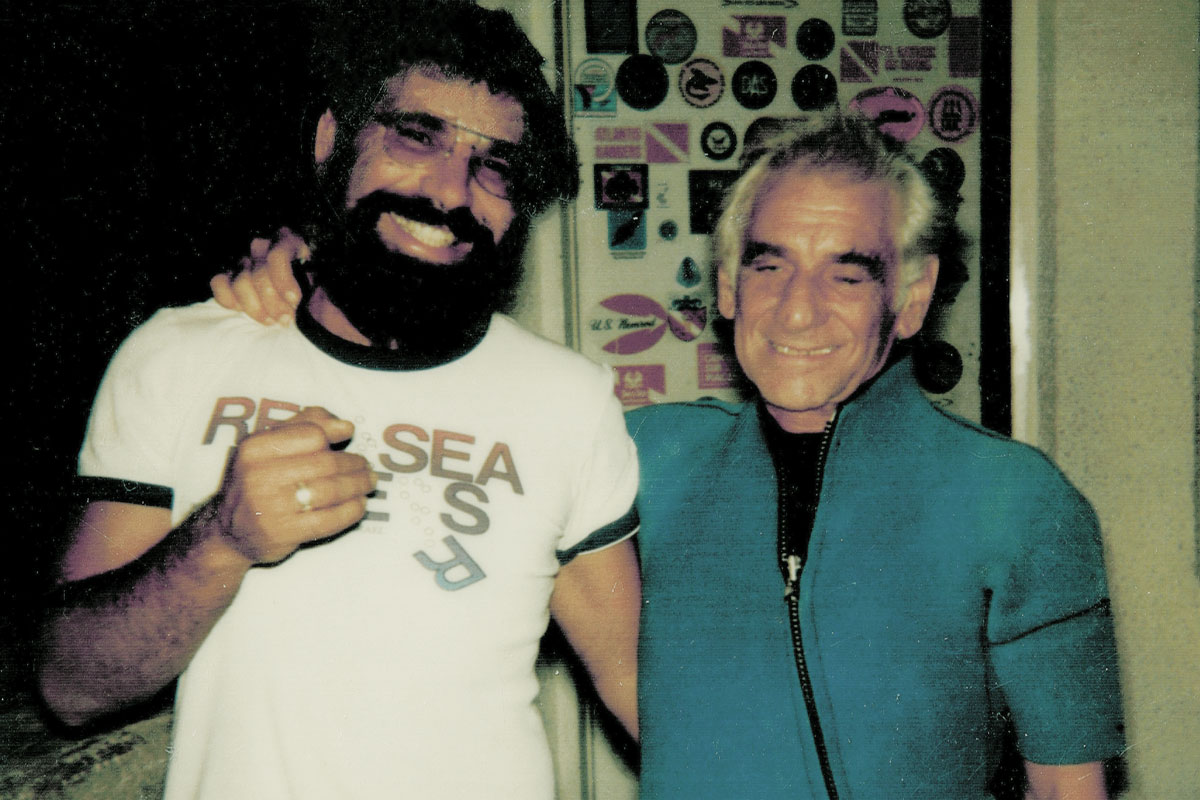

Howard Rosenstein with Leonard Bernstein (photo by David Doubilet)

Howard Rosenstein with Leonard Bernstein (photo by David Doubilet)

Bernstein’s beaming face could have lit the way as we made the return trip back to Sharm.

I should not have been surprised by Bernstein’s impetuosity. Years before, I was in Tel Aviv to meet the Doubilets for a previous National Geographic article when I heard that the conductor was in town. Shortly after I left a message for him at his hotel, he called back and asked if I could arrange a day of sailing out of the Tel Aviv marina, which he could see from his hotel room. I set something up for the next day and invited the Doubilets to join us. Unfortunately, the skipper canceled in the morning because of rough seas.

When I called Bernstein with the bad news, he said he was disappointed but still hoped to get down to Sharm after he finished his concert tour. As we were chatting, I happened to mention it was my birthday. To celebrate, he invited the Doubilets and me up to his penthouse suite. He even ordered champagne and a birthday cake from room service. After salutations, blowing out the candles, and a few glasses of the bubbly, Bernstein sat down at the grand piano that the hotel had supplied him and asked me what I would like to hear. I was dumbfounded: a command performance by the great maestro in my honor!

I struggled to think of something fitting, hoping to come up with the name of a piece he had played at one of his televised youth concerts I had loved watching as a child growing up in Los Angeles. In desperation, I blurted out “West Side Story.” Bernstein smiled, nodded his head, and played a medley from my favorite musical. For an encore, he performed the Yiddish classic “Yidl mitn fidl” (“Yiddle with His Fiddle”) and sang along in Yiddish, which he had learned as a child in the Boston area. When he finished, we gave him a laughter-filled standing ovation. He bowed as if he had just concluded a gala performance with the New York Philharmonic.

Back to the Sinai summit, Sadat and Begin were due to fly in the next day. As host of the National Geographic team, I was given press credentials and allowed to accompany the journalists to the airport for Sadat’s arrival. The press was fenced off on an elevated platform, but I managed to get some great shots of Begin greeting Sadat. Afterward, we followed the motorcade into town. The summit site was a large, empty building next to our diving center. Locals had dubbed it the “White Elephant,” since it was built for some project that had yet to materialize.

While Begin and Sadat were freshening up in their hotel rooms, an event organizer approached me in a panic. He told me no one had remembered to get furniture for the summit. I had my crew rush over chairs and tables from the diving center restaurant. They were in place just minutes before Begin and Sadat arrived.

The meeting made headlines around the world, as had every step of the peace process since Sadat’s visit to Israel in 1977. Ringside as an official press photographer, I captured some great candid shots of the meeting. As I watched leaders take their seats, I nervously chuckled at the thought of our flimsy bamboo chairs collapsing and setting off an international incident.

A few hours later, the excitement was over. The leaders and their delegations flew back to their respective capitals of Cairo and Jerusalem; the media collected their gear and prepared their reports; and we resumed our routine of taking tourists diving in the Red Sea.

In retrospect, I doubt the summit accomplished much beyond providing Begin an international photo op in advance of the Israeli elections later that month. Besides, Begin was likely preoccupied at the time with a secret operation that would take place a week later and a 1,100 kilometers away: Israel’s attack on Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor.

The day following the summit, Bernstein had to return to Tel Aviv and asked me to give him a lift to the airport. As we headed north, another jeep cut across our path from a side wadi. I had to swerve to avoid it. I was furious! Ours was the only car on the road, so why did this jerk have to cut us off?

Both vehicles stopped within centimeters of one another. Next thing I knew, Bernstein was jumping out of his seat and embracing the passenger from the other Jeep. I wondered what the hell was going on.

Turns out, the passenger was Daniel Barenboim, another of the world’s most famous musicians. To think of what would have happened had our Jeeps collided. I envisioned the headline in the next day’s New York Times:

“Famous maestros killed in Sinai jeep crash.” And I, as one of the drivers, would have become a footnote in history.