November 2023

Chris Long

One of 2023’s best and most-discussed films was Oppenheimer, the three-hour epic biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, directed by Christopher Nolan and starring Cillian Murphy. The film tells the story of the Jewish-American theoretical physicist, scientist, and director of the Manhattan Project, who became infamous in world history as the ‘father of the first atomic bomb’. Based on the biography American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, the biopic explores the life and work of Oppenheimer, focusing on two major events, one world-altering and the other deeply personal: the building of the atom bomb at Los Alamos and its first detonation at the “Trinity Test”, on July 16, 1945; and the hearings of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, which resulted in the removal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance in 1954. The latter event destroyed his reputation as a public intellectual and American hero due to his controversial associations with members of the Communist Party. The film is both an exciting historical drama about a pivotal moment in world history and a detailed character study of one of history’s most brilliant, controversial, and enigmatic men.

For generations, Oppenheimer’s character has been shrouded in mystery and mystique. Who was Oppenheimer? How did he feel about his role in the dawning of the atomic age? What were his regrets about the reshaping of our world? The film is an attempt to set the record straight on some of these questions. However, for those of us who are interested in learning more about this remarkable historical figure, you may be surprised to find answers closer to home than you might think.

In the voluminous archives of McMaster University, there are a significant number of archival records related to Oppenheimer, particularly his life following the 1954 security hearings and his relationships with members of the anti-nuclear movement formed in reaction to his life’s work.

In early 1962, Oppenheimer delivered a series of lectures at McMaster under the title “The Flying Trapeze: Three Crises for Physicists.” These lectures were an entry into the famous ‘Whidden Lecture’ series, founded in 1954, which has hosted great thinkers and luminaries such as Northrop Frye, Noam Chomsky, Tom Stoppard, and A.J. Ayer. The late Rabbi Bernard Baskin also delivered two lectures for the series in 1978.

Oppenheimer’s Whidden lectures were recorded and published as a book under the same name which is held within the rare book library of the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University. It can be requested for viewing in the McMaster Archives’ reading room, located in the lower level of Mills Library. The reading room is open to members of the public, by appointment.

In his McMaster lectures, Oppenheimer reminisced about the U.S. government’s argument for using the bomb against Japan, that is, as an effective alternative to a costly and painful land invasion. He stated, “Nevertheless, my own feeling is that if the bombs were to be used, there could have been more effective warning and much less wanton killing than took place … Those are the days when we all drank one toast only: ‘No more wars.’”

Oppenheimer’s lectures demonstrated his belief that the revelation of atomic power would necessitate international collaboration to monitor and control it: “We think of this as our contribution to the making of a world which … with all its variety, freedom, and change, is without nation states armed for war and above all, a world without war.”

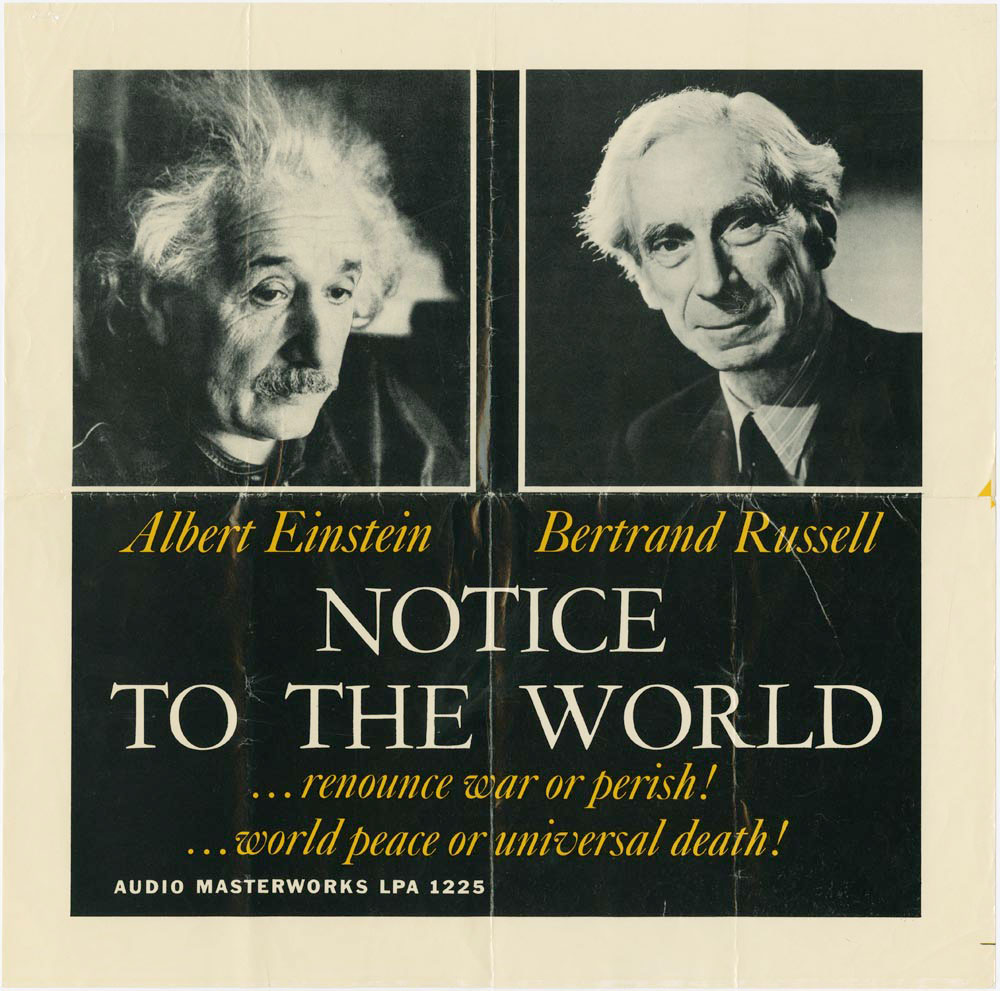

A second archival document, also found within McMaster’s holdings, complicates the above depiction of Oppenheimer as anti-nuclear. Within the archives of the philosopher and peace activist Bertrand Russell, whose archives were acquired by McMaster in 1968, there are several documents related to an anti-nuclear conference organized by Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein at Pugwash, Nova Scotia in 1957. Oppenheimer declined their invitation to the conference, stating that he was “somewhat troubled when [he] looked at the proposed agenda” which he felt to be overly critical of the US nuclear program as it was at the time.

His biographers saw this incident as revealing. Although Oppenheimer was against the growing threat of nuclear gamesmanship, he would not go as far as truly anti-nuclear activists such as Russell, Einstein, and his former colleague at the Manhattan Project, Joseph Rotblat. (Rotblat, a Polish-born Jewish physicist, is famous for being the only scientist to leave the Manhattan Project in 1944, when intelligence revealed that the Germans had no chance of successfully building an atom bomb.)

Within the Russell archives is a letter from Oppenheimer to Russell for his 90th birthday, in 1962. Despite their earlier disagreement, he writes admiringly to the elder scholar, “For those of my generation, our world would have been far emptier of these great qualities without your presence and your work.” (Oppenheimer and Russell knew each other for years, both lecturing at Princeton at the same time. According to several sources, Russell was dining with Oppenheimer when he received notice that he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950).

The birthday letter is the only signed letter from Oppenheimer in McMaster’s archives. The letter, as well as the records related to the Pugwash Conference including signed letters from Albert Einstein, can be requested for viewing at the Bertrand Russell Archives at 88 Forsyth Ave N. Those interested in this material or any of the other incredible resources held by McMaster Archives can book an appointment by emailing at [email protected].

Chris Long is an archivist at McMaster University.

Captions:

i. J.Robert Oppenheimer delivering a lecture at McMaster University in 1962. Courtesy of the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University

ii Leaflet, 1955. Courtesy of the Bertrand Russell Archives, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University.